During my 5 years at Playcentre, we sometimes had to deal with challenging behaviour from our 0-5 year olds (from their parents sometimes too, luckily way less often!). We made a point of discussing how we can better deal with these situations at our meetings. I led one of these talks and decided to share its content hoping that it will help other parents on their parenting journey. I can see it being useful for a lot of different group settings with pre-schoolers and parents involved, e.g. Playcentres, community playgroups, family groups etc. The basis for the advice is mostly based of the Playcentre training programme, which leads to a NZQA accredited level 4 certificate in early childhood education. Happy reading and good luck on your journey!

This blog post will cover the following:

- Developing brains

- Behaviour is communication

- The Magic List for meltdown prevention

- Dealing with melt downs

Developing brains

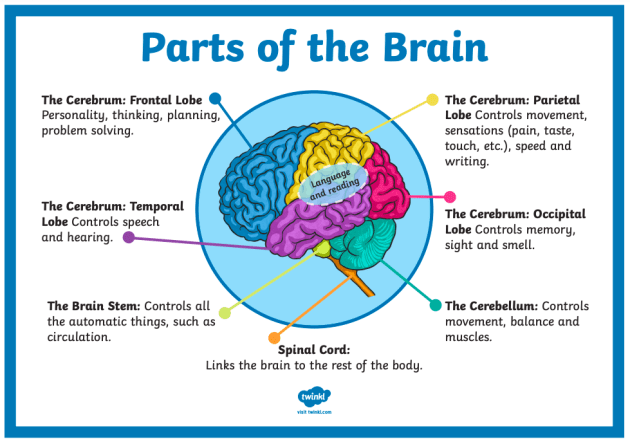

Whenever we talk about challenging behaviours with regards to children, we have to take into consideration that their brains are still developing. The frontal lobe, which is responsible for executive function such as rational thinking, planning, problem solving, behavioural control and decision making, is what we want our children to develop in order to be able to deal with stressful situations in an acceptable way. However, our brain gets built from the bottom up. The frontal lobe develops at the very end and over time! I Know! A pretty infuriating order, but bear in mind that there are lots of connections to construct…

A brain matures at around 23 years of age, some children will develop certain areas of the brain sooner or later depending on a lot of influencing factors such as whether you’re a first child or second born child, gender, external influences, experiences, interests, family surroundings etc.

Even if children sometimes seem very confident and competent at what they’re doing, it doesn’t mean that they will be able to cope by themselves when stressed. They need consistent guidance and support to get through challenging situations.

Behavious is communication

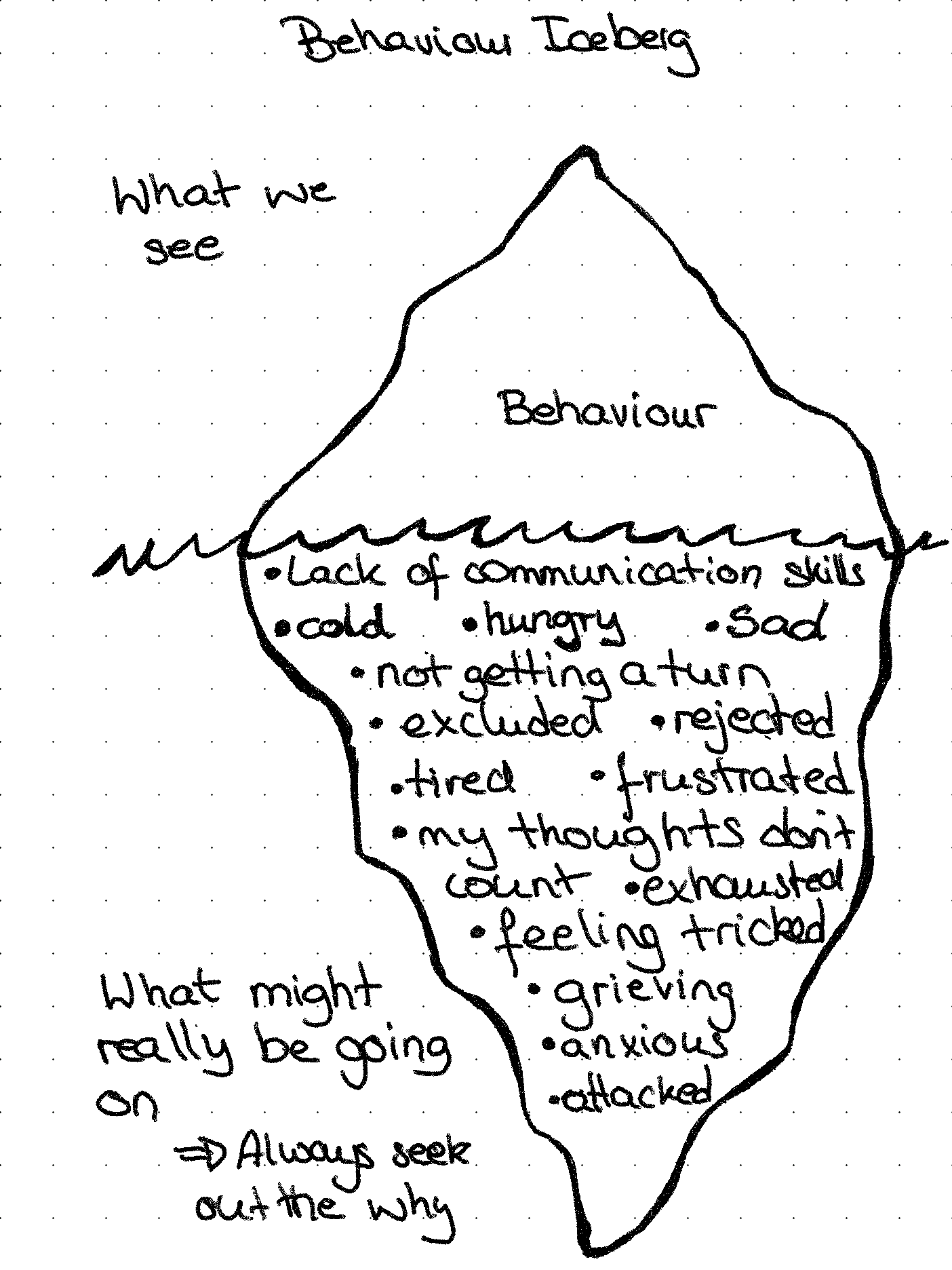

The second thing that comes to mind is that the behaviour we see often is just the tip of the iceberg. We see that a child hits, bites or doesn’t share. But underneath there could be a lot of influencing factors.

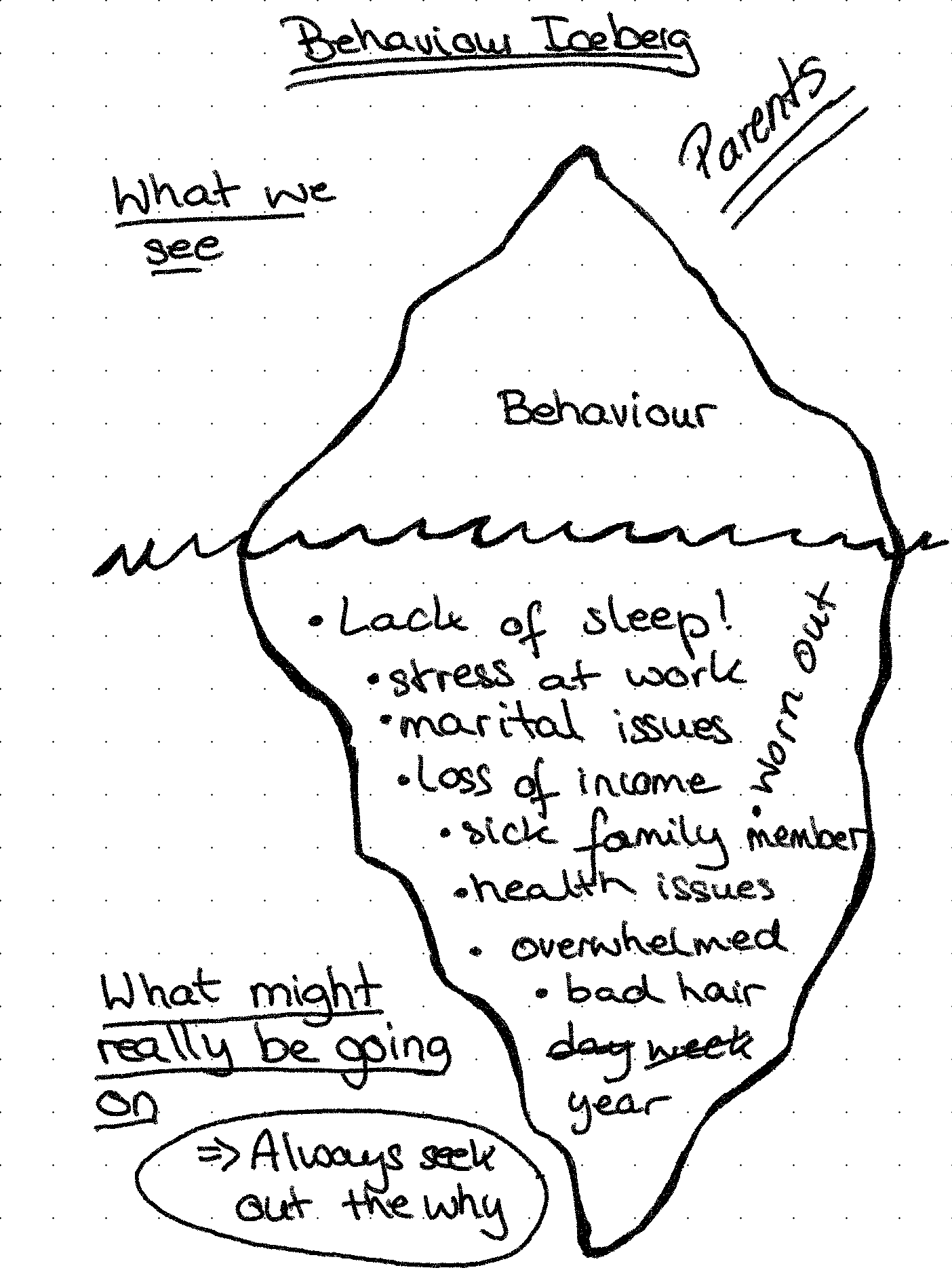

Now this is not only true for the children but also the parents in our community. Often if someone is not getting their job done or acting inappropriately in some way, instead of judging them from the get go, try to take a supportive approach. Ask them if they're doing ok or why this seems to be a struggle for them. They might have their own iceberg which could look like this:

They might have lots of pressure at work (as many of us work part time or even full time), house renovations, health issues, marital issues, burnt out from being a parent, lack of sleep, be over committed…all kinds of things really, often simultaneously… Depending on the person they will be happy to share what is going on or not. So instead of jumping to conclusions, try to be supportive and kind to each other. Who knows, one day you might need some support yourself...

Coming back to the children, we need to dive deep, observe (especially if it's a recurring behaviour) and try to understand the cause whilst supporting the child to understand, express and regulate their emotions.

So how do we guide them through it? First of all, try to prevent meltdowns whenever you can with the following strategies.

The magic list for meltdown prevention

11 strategies to help with meltdown prevention in early childhood

At Playcentre this is what we turned to when it came to preventing our kids from melting down:

- Supervision: Sometimes our 4 year olds can seem very capable in many ways and it can seem that they don’t need that much supervision (especially compared to a 1 or 2 year old). But when reaching that age, they might also feel a bit like they're the boss. If we don’t supervise them appropriately, situations can arise where children get excluded from play, no proper turn taking happens, things are being said that aren’t nice etc. So even if there’s a group of children who don’t want you to be actively involved in their play, it is always good to have at least one adult positioned near to them who can keep an eye and ear out just in case something does comes up. Doing that will also help to extend their play and thus keep them engaged. When they’re engaged they come up to less mischief.

- Build supportive relationships – Children will listen to you better if they know you and have had positive and meaningful interactions with you previously. So when you’ve got a minute to spare, as you’re child is engaged in some activity elsewhere, try to make some little friends in addition to your grown up friends. This will help with our collective efforts to guide behaviour positively.

- Food, sleep, drinks, cold - Cover the basics – if a child is hungry, tired, or thirsty or cold it can affect them in a major way and result in tantrums or acting out. Even if the child says that they're not hungry, but you know that they haven't eaten for a couple of hours this will most likely be one of the causes. So maybe try to coax them away from the situation with a cuddle and a story and then sneak in the yummy lunch box / sweater /drink.

- Anticipate situations, divert/redirect - If you see that multiple children are interested in the same activity, provide more resources where possible (e.g. another zippie, swing, tool etc.). If that is not possible you can try to redirect children to other activities, this especially works with the younger ones. Redirecting to an activity that feeds the same urge can also work well, e.g. offering a child who is throwing equipment, a soft ball to throw, or cotton balls dipped in paint he can throw on a paper wall. Another example is redirecting overly boisterous games or game fighting to an energy releasing activity such as running timed laps or letting them bump over soft foam shapes. This is also where planning comes in – we need to make sure our children are fully engaged through planned activities and need to make sure that these activities actually happen as planned. No better reason to act up than boredom.

- Get support – ask for help, talk about it - This is quite important. When you encounter a child’s behaviour that has affected you or your child, don’t keep it to yourself. If you don’t bring it up, smaller issues can compile into a big mountain that might feel insurmountable and end in an outburst. At Playcentre we used to run an end of each session evaluation where you could bring these challenges up. In other settings it might be a coffee date with the parents or an informal conversation with the parties involved. The parents involved on both sides can work on approaches of how to deal with the behaviour. You might find that the child's parent is already aware of the problem and has a specific way to deal with it that he found to be effective. Or you might work out something together and also let other parents know about how to handle this behaviour. Taking the cooperative approach ensures that all parties feel heard and that the child gets a consistent response from all sides. This is important as the child will be guided into the same direction by everyone and will learn faster.

- Give specific praise - Us adults tend to give our children a lot of feedback with regards to what our kids shouldn’t be doing. However, it is more effective to catch them in a situation, where they act in a desirable way and to reinforce the positive behaviour then and there in a specific way. E.g. “I love how you made sure that your little brother got a turn”. “I really liked how you made sure that all the children were included”. If you do this in front of them that is great, but if they catch you talking about this positive behaviour to someone else, it will have 10 times the impact. Unfortunately that also works the other way around - when you’re talking to others about their undesirable behaviour, it can damage their self esteem. So be careful of what you say in front of them, they soak it all up.

- Use positive language – Say what you want them to do, not what you don’t want them to do. Our brains can't really do negation, so if you tell them do not throw the sand, the brains first impulse is to act on “throw the sand”. My marketing prof used to say "If you’re driving alongside a road with lots of trees and suddenly loose control of your car, think 'gap gap gap'. If you think 'don’t hit a tree', you will hit a tree…". So try to use positive language e.g.: A child throwing sand in peoples faces: “keep the sand low”, hitting/shoving – “keep your hands to yourself" or "gentle hands,”; biting – “teeth are only for eating food”; a child standing on chairs/tables – "feet on the ground" etc.

- Point out natural / logical consequences - This does not relate to threats like: "if you don’t do this, then you won’t get screen time today.." If you threaten them children won’t think about their behaviour, they’ll only think about how mean you are. This point rather refers to natural or logical consequences. for instance: "X will be really sad if he doesn’t get a turn."; "If you keep hitting this, it will break and we won’t have any to play with in future."; "If you don't put a jacket on you will feel really cold" etc.

- Provide quiet time - Sometimes children can get overstimulated. Try to see whether you can see a pattern, e.g. do meltdowns always happen around the same time of day? Then plan for quiet activities for that time of day if you can.

- Time in - If a child can no longer control themselves offer food or reading a story with them. Or say “X why don’t you come to me and have a little sit down together. We can watch what the others are doing”.

- Change of scene “I can see that you’re getting really frustrated, why don’t we come back later to this activity.”

Dealing with meltdowns

You've done your best to prevent it from happening, but, as I often used to say, the universe has struck again and you do have a meltdown on your hands...Yikes! What to do??

- Hugs, caring - Children's brains are unable to regulate themselves, so showing them that we care with hugs, kisses or other gestures that give them comfort will help their body to release the right hormones for them to calm down.

- Get down to eye level - getting down to their level or even lower, will help you better connect with them. Otherwise they might feel that you're towering above them.

- Mirror their feelings. Acknowledging their feelings will help them to calm down as well; e.g. "I can see that you are really upset that he took the only blue truck." (I found that this also works well with adults.) Naming their emotions will help them to articulate these feelings better in future.

- Link to build rapport - Link their behaviour to what you know about the child, thereby validating their feeling. E.g. "That makes sense, I know that your favourite colour is blue." Note, that you can sympathise with their emotion even if you don't agree with their behaviour.

- Get them to calm down before you get into the nitty gritty - While the kids are in a state of high alert they won’t be able to act rationally or learn from the situation. That goes for both the child that got hurt and the one that acted out. So getting them to calm down is important before we talk about what has happened, why the behaviour is not acceptable, how it has affected the other party. Avoid blame, rather try to give their emotions names and work out ways with them in which they could cope with the situation better in future.

- I wonder... Instead of presenting them with a solution to the problem straight away, try saying "I wonder what we could do to solve this" or "I wonder how we could make your friend feel better again". Then pause and give them some time to think about this. This encourages the child's problem solving skills and will also make him own his solution to the problem. They might not come up with something the first time around you're asking them to problem solve. That's fine. But the more often they're prompted to look for solutions in such situations the better they'll perform over time.

- Guide - If they've tried and they come up empty, guide them through it. e.g. Maybe we could try to find another blue car / use the blue motorbike instead / wait until he's finished playing with it etc...

- Stay calm - This one can easily be forgotten when the kids get loud and you're trying to be heard. But it is counterproductive to match their emotions, as it will only make matters worse. So try to use a quiet voice instead, be their rock... After all it's their meltdown, not yours. Reassure them that you are here for them when they're ready to work on a solution.

Best of luck!

Cover Photo by Alexandr Podvalny on Unsplash